A mysterious 300-million-year-old sea creature, known as the ‘Tully monster’, definitely did not have a backbone, a new study has claimed.

Scientists have been debating the morphology of Tullimonstrum gregarium since its fossils were first discovered in the 1950s.

The ‘undersea alien’ had eyes on stalks and teeth on the end of a trunk, and grew up to 14 inches (35 cm) in length.

But whether it was a vertebrate or invertebrate has been a point of contention, with evidence being found to suggest both.

Now, researchers at the University of Tokyo in Japan say that the Tully monster’s body parts once thought to indicate a backbone are not actually as they seemed.

A mysterious 300 million-year-old sea creature, known as the ‘Tully monster’ (pictured in artist’s impression), definitely did not have a backbone, a new study has claimed

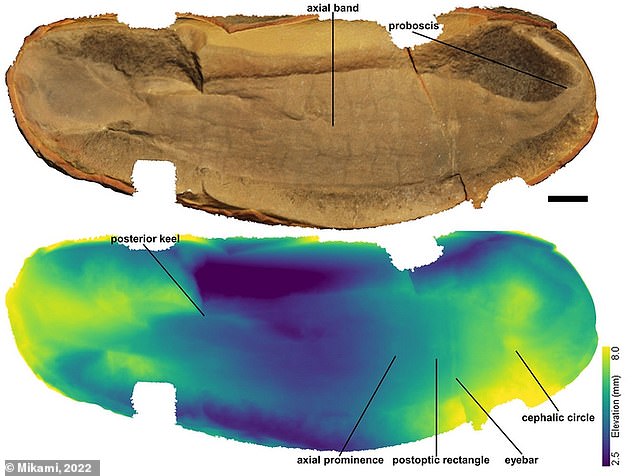

Colour-coded depth maps (pictured) enabled the researchers to thoroughly investigate the structure of the Tully monster and other fossils from Mazon Creek, Illinois, USA

‘We believe that the mystery of it being an invertebrate or vertebrate has been solved,’ said first author and doctoral student Tomoyuki Mikami.

‘Based on multiple lines of evidence, the vertebrate hypothesis of the Tully monster is untenable.

‘The most important point is that the Tully monster had segmentation in its head region that extended from its body.

‘This characteristic is not known in any vertebrate lineage, suggesting a nonvertebrate affinity.’

Fossils of the Tully monster were first discovered in Mazon Creek, Illinois, in 1955, by amateur collector Francis Tully.

They are thought to have lived in the muddy shallow waters around the coast that once sat over that area of Illinois 300 million years ago.

When they died they were covered in silt and became encased in the hard rock that later formed.

The fossil beds at Mazon Creek are one of the only places where the conditions were right to preserve the soft-bodied creature in a fossil before they decayed.

Their eyes sat at each end of a long rigid bar across the top of their heads and they had tail fins.

Most strangely, they had jaws at the end of a long proboscis, or trunk, suggesting they ate food hidden deep in the silt of the estuary or within rocky nooks and crannies.

This bizarre anatomy has made the Tully monster difficult to classify and, in 2016, a study from Yale University put forward evidence to suggest that it was a vertebrate.

Thousands of fossils of the creature have been unearthed in hard rocks dug out of coal mining pits in Mazon Creek, Grundy County, Illinois

Fossils of the Tully monster (pictured in artist’s impression) were first discovered in Mazon Creek, Illinois, USA in 1955, by amateur collector Francis Tully

Analysis of some fossils revealed what appeared to be a rudimentary spinal cord made of stiffened cartilage, known as a notochord.

They also claimed it contained other internal organ structures, such as gill sacs, that identified it as a vertebrate, and that its teeth resembled those of the lamprey fish, which also has a notochord.

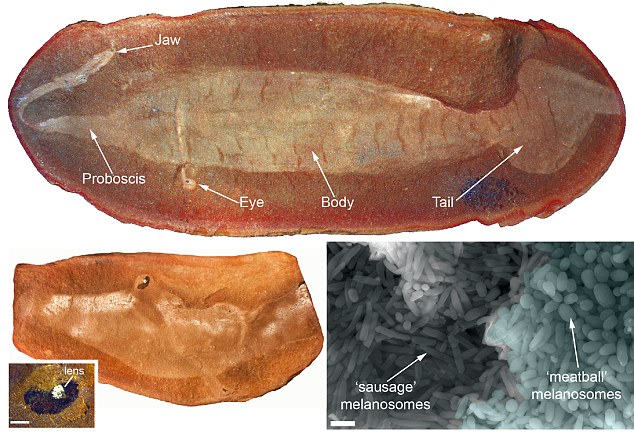

Then, scientists at the University of Leicester claimed to identity fossilised granules in the creature’s eyes that could only be the pigment melanin.

They saw that the pigment-producing cells called ‘melanosomes’ were of two different shapes, which is something only seen in vertebrates.

If these two studies are correct, then the Tully monster could fill a crucial gap in the evolutionary tree of vertebrates.

However, a year later, a team from the University of Pennsylvania claimed they were wrong.

They said that you can’t discern the Tully monster’s internal structures from its fossils, and that lampreys also do not resemble them.

While the melanosomes do suggest it was a vertebrate, they added that many invertebrates, such as arthropods and cephalopods like octopuses, also have complex eyes.

‘It’s not too much of a leap to imagine Tully monsters could have evolved an eye that resembled a vertebrate eye,’ they said.

They concluded that none of the more than 1,000 Tully specimens examined in the two 2016 studies appeared to possess structures believed to be universal in aquatic vertebrates.

But a 2019 study from University College Cork disputed this again, saying that the ratio of zinc to copper in the creature’s melanosomes were more similar to that of modern day invertebrates than vertebrates.

In 2016, scientists claimed to identity fossilised granules in the Tully monster’s eyes that could only be the pigment melanin. They saw that the pigment-producing cells called ‘melanosomes’ were of two different shapes (‘sausages’ or ‘meatballs, pictured bottom right), which is something only seen in vertebrates. Above: Fossil of Tully monster

For the new study, researchesrs studied more than 150 fossilised Tully monsters and over 70 other varied animal fossils from Mazon Creek using state-of-the-art imaging technologies. Pictured: An illustration depicts what Mazon Creek may have looked like 300 million years ago, complete with Tully monsters (the two small swimming creatures), a large shark and a salamander relative. The new study claims that the identity of the monsters is still up in the air

But, for their new study, published in Palaeontology, the Tokyo-based researchers wanted to put this debate to bed.

They studied more than 150 fossilised Tully monsters and over 70 other varied animal fossils from Mazon Creek using state-of-the-art imaging technologies.

This involved using lasers to make colour-coded depth maps of their surfaces, and X-Rays to create 3D models of their trunks.

This data revealed that certain, previously identified structures are not actually comparable with those of vertebrates.

These include a tri-lobed brain, specific brain cartilage, fin spines and ‘myomeres’ – muscle segments that offer greater body control.

Furthermore, the teeth on its trunk are not comparable to those of the lamprey either.

The team are therefore confident that Tully monsters were not vertebrates, but are still not sure what class of invertebrate they fall into.

They could be a nonvertebrate chordate, which have a notochord but lack a true backbone, or a protostome, like an earthworm or a snail.

Mr Mikami says that the difficulty had in classifying the Tully monster highlights how many interesting, soft-bodied creatures may never have been preserved as fossils.

‘In this sense, research on the fossils from Mazon Creek is important because it provides paleontological evidence that cannot be obtained from other sites,’ he said,

‘More and more research is needed to extract important clues from Mazon Creek fossils to understand the evolutionary history of life.’

THE TULLY MONSTER AND ITS BACKBONE

In 2016 experts said the Tully Monster was likely a predatory vertebrate related to lamprays.

Paleontologists at Yale University showed the creature had a stiffened rod of cartilage that supported its body and gills. This means it was a predatory vertebrate, similar to primitive fish.

US Geological Survey sea lamprey expert Dr Nick Johnson demonstrating the ridge of tissue, called a rope, along the back of a mature male sea lamprey

Victoria McCoy, a palaeontologist who conducted the research at Yale Univesity, now based at the University Leicester, analysed the morphology and preservation of the animal.

Using powerful analytical techniques, such as synchrotron elemental mapping, which illuminates the physical features by mapping the chemistry of the fossil, she was able to unravel its features.

Her team discovered the animal had a rudimentary spinal cord, known as a notochord, and gills, which had not been previously identified in the fossils.

Source: dailymail