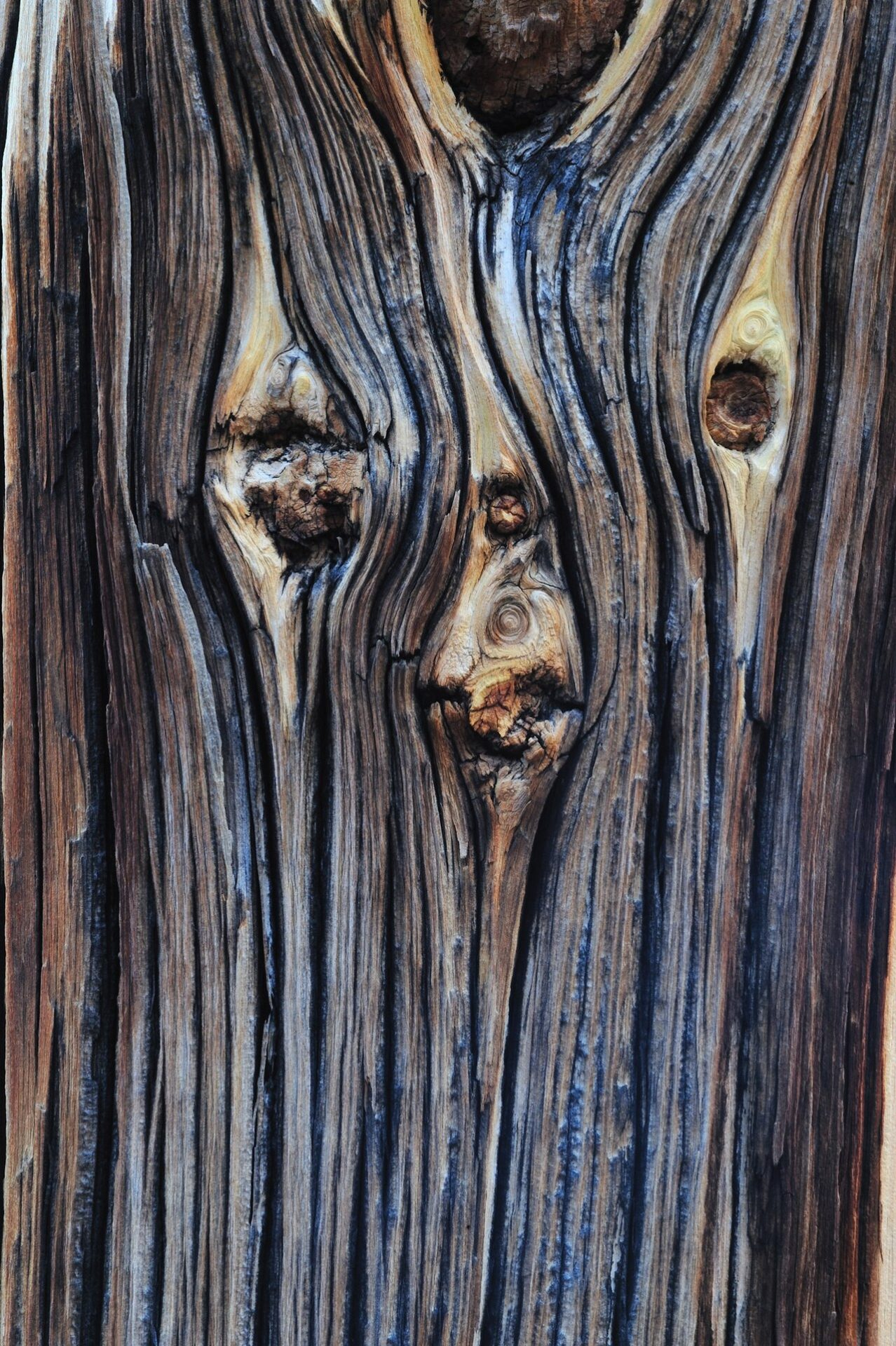

“Methuselah,” a bristlecone pine in California long considered to be the world’s oldest tree. Image Credit: Yen Chao, Flickr

High on a ridge in California’s Eastern Sierra, a gnarled bristlecone pine known as Methuselah has reigned over almost five millennia’s worth of snowy winters and blazing summers. Methuselah, whose crooked and weather-beaten boughs make it look more like a sculpture than a living thing, is estimated to be 4,853 years old, based on data from a core sample taken in 1957—making it the oldest tree in the world.

Until now. This year, an upstart competitor has appeared to challenge California’s grizzly old-timer. Nicknamed Alerce Milenario, or Gran Abuelo, which means great grandfather in Spanish, it sits in a humid valley outside La Unión, Chile. As reported in Science in May, researcher Jonathan Barichivich says new data suggest the tree might hold a new record: 5,484 years old. (That record excludes clonal trees that share root systems, like aspen colonies, Science specified. In the search for the oldest tree, scientists focus on individuals with just one trunk.)

Gran Abuelo is an alerce, or Patagonian cypress, a type of conifer related to giant sequoias and coast redwoods. Like their Californian cousins, alerces can grow to very old age; at least one other alerce in southern Chile has been dated at 3,600 years old. That makes the species the second longest-lived in the world—older than sequoias but not quite at the bristlecone pine level. And Barichivich knows alerces well. He grew up around them, including Gran Abuelo, since his grandfather and mother both worked as rangers in the park where Gran Abuelo grows. He says his grandfather discovered the tree around 1972. “It’s a tree that’s very, very close to our hearts,” he told Science.

Standard practice in dendrochronology, the science of determining tree age, involves counting rings from a thin core taken from the living tree, then comparing those rings to patterns in cores from trees nearby. But Barichivich ran into a problem: Gran Abuelo’s trunk was so wide that his increment borer, the instrument usually used to take age cores, could not reach all the way through. And while in similar cases some dendrochronologists might take samples from the roots to supplement or confirm available data, Barichivich was concerned that that might damage the tree’s roots, which have already struggled under the footsteps of curious tourists coming to see their arboreal elder. “It’s not the point to make a big hole in the tree just to know that it’s the oldest,” he told Live Science. “The scientific challenge is to estimate the age without being too invasive to the tree.”

Intead, Barichivich used statistical modeling to estimate Gran Abuelo’s age, drawing on data from fully cored alerces nearby and incorporating possible growth rate variation and fluctuations caused by climate and environment. The result that the model suggested shocked him. The absolute oldest the tree might be was 6,000 years, it said. There was an 80% chance that the tree was over 5,000 years old, with an overall estimated age of 5,484. “It was astonishing,” he told Science.

Though Science reported on Barichivich’s findings in May, he has yet to publish them fully in a peer-reviewed journal. His fellow dendrochronologists have therefore greeted his claims with a mix of intrigue and doubt. “I fully trust the analysis that Jonathan has made,” Swiss Federal Institute of Technology dendrochronologist Harald Bugmann told Science. “It sounds like a very smart approach.”

But others remain skeptical. “The ONLY way to truly determine the age of a tree is by dendrochronologically counting the rings, and that requires ALL rings being present or accounted for,” Ed Cook, a founding director of Columbia University’s Tree Ring Laboratory, told the publication via email. Similarly, Peter Brown, who has produced a database of the oldest trees on Earth and serves as Guinness World Records’ consultant on the oldest tree, told The San Francisco Chronicle that the project is “awfully interesting,” but he wants to see the details before coming to any conclusions. Plus, he pointed out to National Geographic, Gran Abuelo’s estimated age is over 1,500 years older than the next oldest alerce, which is a pretty big jump. (Barichivich stands by his estimate, citing the “growth-lifespan tradeoff” to Live Science, a theory that posits that slow-growing species tend to live longer—and alerces grow slower than both sequoias and bristlecone pines.)

Ultimately, Barichivich emphasizes that “the objective is to protect the tree, not to make headlines or break records.” He told Newsweek he was going public with his research out of concern for Gran Abuelo’s wellbeing, estimating that only 28% of the tree is still alive. (Trees possess a remarkable ability to compartmentalize decay, walling off areas that have been invaded by fungi and microorganisms and prioritizing growth in other areas.) Not only do tourists come too close for comfort, he said, but the tree is currently encircled by a platform that is crushing the remaining living roots. He and his colleagues would like to see the park where the tree lives erect a protective net and move the walkway further from those roots. “To me, this tree is like a family member,” he said. “Seeing him like this is breaking my heart.”

Meanwhile in California, the guardians of Methuselah told The San Francisco Chronicle that they’re “not concerned” about the southern challenger but are intrigued by Barichivich’s innovations. “Perhaps there are other older trees out there waiting to be discovered with this new potential dating method,” ranger Andrew Kennedy said.

That may include in Methuselah’s own backyard. In 1959, a tree ring researcher from University of Arizona collected cores from several of Methuselah’s ancient neighbors, suspecting some might be even older—but died before he could complete his analysis, The Chronicle reports. Then in 2010, another researcher restarted the project, finding one core that seemed to suggest a still-living tree might be 5,062 years old. But that researcher died before the work was complete as well—and then the cores were lost.

Meanwhile, these most ancient of trees, having witnessed countless 𝐛𝐢𝐫𝐭𝐡s and deaths and virtually all of modern human history, live on.